Shakespeare’s villains are often victims of stigma based on social identities written into their bodies—Richard III and Caliban’s physical deformities, Aaron and Othello’s black skin, Don John and Edmund’s illegitimate births, Shylock’s Jewishness, Falstaff’s obesity. Since the 1980s, Shakespeare scholars have explored the characters marginalized because of gender, race, religion, sexuality, nationality, disability, class, age, and intersectionalities among such categories. Less studied is the structure of stigma that spans these identity categories—the process of making, managing, and dismantling the meanings of discredited social differences.

The world was changing, technology bringing different cultures into closer contact, science disputing theological traditions about the meanings of bodies. Yet the politics of narcissism – love of what looks like me – reigned supreme. Onto this scene burst Shakespeare, whose plays suggest that social interaction between stigmatized people and stigmatizers will always be fraught, imperfect, tragicomic, loaded with guesswork about attitudes and biases, even when attempts at reparations are made. Historicizing stigma in earlier English literature and culture, theorizing it with modern social science, this book shows it to be central in Shakespeare’s artistic vision, and Shakespeare to be central in the history of stigma.

Publications

|

The Figure of Stigma in Shakespeare’s Drama |

Hath Not a Jew a Nose? Or, the Danger of Deformity in Comedy |

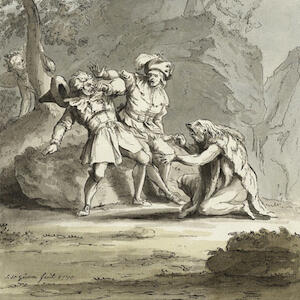

"Savage and Deformed": Stigma as Drama in The Tempest |

Overview

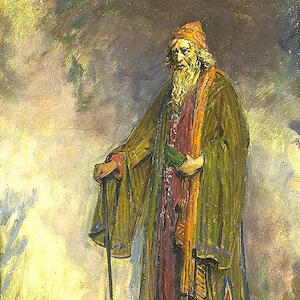

Shakespeare's first great villain, Richard III, is “as crooked in his manners as in his shape.” His next great villain, Aaron the Moor, “will have his soul black like his face.” And his last great villain, Caliban, is “as disproportion’d in his manners as in his shape.” What is the meaning of bodily difference in Shakespeare’s stories? Why is it so closely attached to villainy? How should we engage with these Shakespearean bodies given their painful legacies in our own age?

This book shows how Shakespeare used stigma—discredited difference affixed to others’ bodies—to structure many of his plays, especially Richard III, Titus Andronicus, King John, The Merchant of Venice, 1 Henry IV, Troilus and Cressida, King Lear, Othello, and The Tempest.

Late in the twentieth century, Shakespeare studies exploded with interest in his representation of people marginalized because of gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, religion, disability, age, and the intersectionalities among them. These concerns are connected in literary criticism because they are connected in life: patterns of discrimination and the experiences of those marked as outside the “norm” resemble and signify each other. As Ania Loomba writes, “Othello and Caliban speak at once to vastly different histories and geographies, and yet together they indicate a shared terrain on which ideas of human difference were reshaped during the early modern period.”

The American sociologist Erving Goffman termed this stigma when arguing that “persons with different stigmas are in an appreciably similar situation and respond in an appreciably similar way.” Drawing especially upon Goffman’s Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (1963) and Imogen Tyler’s recent critique of him in Stigma: The Machinery of Inequality (2020), I argue that stigmatized Shakespearean characters—dubbed “others” by W.H. Auden in 1948, “strangers” by Leslie Fiedler in 1972, and “outsiders” by Marianne Novy in 2013—are quite different in their differentness, but they are alike in that they never get to present themselves to others (including audiences) for unbiased interpretation. They are always already interpreted by cultural stereotypes. They can only define themselves through and against those stereotypes. Thus, social prejudice becomes a mental struggle, a rhetorical joust, and an opportunity for the stigmatized character to either disprove or exploit preconceived notions. The scramble to define the identity of a stigmatized character, involving both themselves and others, is one of the most powerful sources of dramatic and conceptual tension in Shakespeare’s plays. Moreover, it tends to be the stigmatized characters with whom modern audiences identify, even though they are explicitly presented as “others,” and it is they who covet and dominate recent interest and criticism.

Shakespeare was the first person to use the word stigma in a consistent and deliberate way in the English language. But stigma was more than a word for Shakespeare. It was a dramatic strategy. It was an approach to the representation of a character—such as Richard, Aaron, Shylock, Falstaff, or Caliban—deemed to be inferior based on some innate aspect of his identity that appears in his body. This book historicizes and theorizes Shakespeare’s treatment of stigmatized characters as a specifically artistic endeavor, not just a case of culture reflected in literature. I show how Shakespeare used Christian allegory, especially the Vice of sixteenth-century English drama, to depict the physical disability of Richard III, and then how Shakespeare worked outward to other kinds of stigmatized identities with Aaron the Moor, Shylock the Jew, Edmund the bastard, and Caliban the savage, among others. Not only was stigma a deep and abiding concern across Shakespeare's entire career, but he has had a surprisingly significant impact on attitudes toward stigma in the modern world. The treatment of stigma in Shakespeare’s drama anticipated the dramaturgical theory of stigma advanced by Goffman in 1963: both Shakespeare and Goffman emphasized the making of the meaning of stigma in face-to-face social encounters, as well as the negotiations of that meaning behind the scenes of stigma.

The stigmatization of marked bodies was a consistent feature of ancient cultures, whether in the form of Greek philosophy, Roman law, or Jewish or Christian scripture. Concepts from those classical works—kalokagathia, physiognomy, monstrosity—were embraced by popular Renaissance texts such as Thomas Hill’s The Whole Art of Physiognomie (1556) and Ambrose Pare’s Of Monsters and Prodigies (1573). Before Shakespeare, if you wanted to address aberrant bodies, you wrote a philosophical treatise or scientific manual. When Shakespeare staged stigma as drama, as rhetoric, as socially constructed, as an event, not an attribute, he both reflected a growing skepticism toward stigma and prompted a change in the way it was addressed—not only in what was said about stigma, but also in howpeople wrote about stigma. After Shakespeare, and to some degree because of him, the most popular medium used to consider physical difference shifted from the philosophical treatise and the scientific manual to the essay.

It is no accident that two of the most influential modern statements on physical disability— William Hay’s Of Deformity: An Essay in the eighteen century and Sigmund Freud’s essay “The Exceptions” in the twentieth—were written by readers of Shakespeare who referred to his Richard III in their essays. It is no accident that the greatest twentieth-century theorist of stigma, Erving Goffman, took his philosophical foundation from the “dramatism” of Kenneth Burke, a Shakespeare scholar. Nor is it a coincidence that the other great twentieth-century commentator on stigma, Leslie Fiedler, was himself a Shakespearean critic and author of the book The Stranger in Shakespeare. The connections between Shakespeare and the modern theorists of stigma are not merely conceptual; they are historical. Progress on resistance to stigma in society was by no means swift, and it is certainly not complete, but Shakespeare initiated an age that acknowledges the meaning of physical differences as circumstantial and perspectival, not absolute. In this regard, Shakespeare helped create the conditions for change in modern attitudes toward physical difference.

Looking to the future, as technology leads both to increasing globalization (bringing different cultures with different ways of life into closer and more frequent contact) and to further medical advances (often promising to “fix” the “errors” of nature as they arise in the human body), and yet these emergent historical phenomena continue to be met with the retrograde politics of narcissism, Shakespeare’s works will remain a valuable resource for posing first-order questions about stigma: Why do so many people hate difference? What, really, is normal? Should we strive to accept or to improve nature? How do we create peace when history demands conflict? How do we repair traditions of prejudice and discrimination? How do we oppose the wrongs of others without mythologizing us vs. them and good vs. evil? These are timely questions as we look ahead, but they are also core questions raised in old Shakespearean plays such as Richard III, Titus Andronicus, The Merchant of Venice, Othello, and The Tempest.