Chapter One

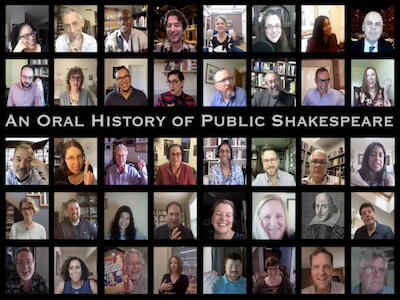

An Oral History of Public Shakespeare

Early-modern theater was a version of what scholars now call “public engagement.” Shakespeare and his contemporaries took sources and ideas from the academia of their time, transformed them into something accessible to a general audience, and created a space for people to think about their lives and times in light of history and creative expression.

Informed by community-based methods of oral history and featured as a keynote address at the 2021 Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference, Chapter One tells the story of Public Shakespeare, drawing from more than 25 hours of recorded interviews with Shakespeare scholars—those who do public-facing work and those who study it. Set on shifting backdrops of the early-modern theater scene, the rise of periodicals during the industrial revolution, the rise of social media during the digital age, and the adjunctification of higher education in the twenty-first century, this chapter collects interviews with historians of Public Shakespeare like Jeffrey Doty, Chris Fitter, Sujata Iyengar, and Uttara Natarajan; with established practitioners like Jonathan Bate, Stephen Greenblatt, Emma Smith, Ayanna Thompson, and Austin Tichenor; and with the next generation, including Brandi K. Adams, David Sterling Brown, Ambereen Dadabhoy, and Rebecca L. Fall. Interviews historicize the rise of institutional programs such as the Folger Library’s Shakespeare Unlimited and The Sundial. Special attention is given to the rise of #ShakeRace, the Twiter hashtag curated by Kim F. Hall, and #PublicShax, created by Fall. The goal is to tell the story of how Shakespeare’s plays started out as a venue of intellectual thought for all citizens of his age, and how that space is being recreated in ours, even—especially—when we’re speaking back to Shakespeare and the bardolatrous powers that hold him up for worship.

Chapter Two

What Shakespeare Scholars Can Learn from Theater Makers About Public Engagement

This chapter opens with a reading of the Measure for Measure put on by the Public Theater’s Mobile Unit in Fall 2019. The cast was all Black women, directed by L.A. Williams. The performance I saw was at the North Brooklyn YMCA—played only a couple of hours before protests rose up against police racism and abuse of force in Downtown Brooklyn.

Based on a talk from the “Public Shakespeare / Public Humanities” panel at the PAMLA conference in 2019, this chapter argues that Shakespeare scholars interested in public engagement could learn a lot from theaters that are “going mobile” to meet people where they are. The analogy to theater helps us envision a Shakespeare studies of, by, and for all people; radically inclusive and fundamentally democratic; engaged with the most important ideas and social issues of our time. This is Shakespeare studies as a public good, scholarship that belongs to everyone. And the analogy to theater also provides some concrete models for putting those principles into action.

To flesh out this idea, the chapter delivers interviews with artistic directors and educational directors at theaters. I spoke with:

-

Antoni Cimolino: Artistic Director, Stratford Festival

-

Olivia D’Ambrosio Scanton: Managing Director, Worcester Brick Box

-

Karen Ann Daniels: Director of the Mobile Unit, The Public Theater

-

Barry Edelstein: Artistic Director, The Old Globe

-

Sara Enloe: Director of Education, American Shakespeare Center

-

Sidonie Garrett: Executive Artistic Director, Heart of America Shakespeare Festival

-

Joseph Haj: Artistic Director, The Guthrie Theater

-

Sara B.T. Thiel: Public Humanities Manager, Chicago Shakespeare Festival

-

Stephanie Ybarra: Artistic Director, Baltimore Center Stage

Quotes from these interviews are arranged to flow into these 22 points:

-

Restructure the profession to incentivize Public Shakespeare.

-

Public Shakespeare is involved in the project of democracy.

-

Public Shakespeare helps make citizens and create communities.

-

Public Shakespeare creates space for human experiences, social connections, and cultural conversations.

-

Public Shakespeare is about the audience, not the academic.

-

Representation matters in Public Shakespeare.

-

Public Shakespeare goes mobile—including local, rural, digital, and global.

-

Public Shakespeare stands for accessibility in all forms.

-

Public Shakespeare seeks out new perspectives.

-

Public Shakespeare thinks creatively about how best to perform scholarship.

-

Public Shakespeare is Bardology, not Bardolatry.

-

Public Shakespeare Trojan Horses politics into Shakespeare and scholarship into politics.

-

Public Shakespeare programs for the moment.

-

Public Shakespeare stops, collaborates, and listens.

-

Public Shakespeare doesn’t knock the hustle.

-

Public Shakespeare runs toward joy, hope, justice, and goodness.

-

Public Shakespeare uses family, fun, and festivity strategically.

-

Public Shakespeare uses time and space creatively.

-

Public Shakespeare plays the long game.

-

Public Shakespeare requires courage.

-

You don’t need to do Public Shakespeare, but don’t get in our way.

-

Public Shakespeare is only as strong as the scholarship it’s based on.

Chapter Three

Public Shakespeare in the Classroom

The Public Shakespeare essays my first-year college students have published come from a writing course called Why Shakespeare?, which takes their minds seriously enough to ask them to be generators, not just consumers, of knowledge. After grappling in our course with Shakespeare’s prominence in modern life, our final meeting is a Public Shakespeare workshop. Students turn their 10-page heavily footnoted research projects about Shakespeare’s modern manifestations into short public-facing essays written with fire and joy. Published essays include:

-

“‘Surreptitious Insurrection’: Shakespeare and the Aesthetics of Revolt in Post-Civil War Nigeria”

-

“What Shakespeare Can Tell Us About School Shootings”

-

“Disney Meets Shakespeare”

-

“The Bard and Bollywood”

-

“Learning to Hate Shakespeare”

-

“The Outcast State: Shakespeare’s Unlikely Connection to Black Subjectivity”

-

“How Shakespeare Helps Us Challenge the Far-Right in Europe”

-

“An Unexpected Concertmaster: How Shakespeare Influenced the Romantic Era”

-

“Shakespeare on Helicopter Parenting”

-

“Black Lives Matter in the Public Theater’s Much Ado About Nothing”

-

“Shakespeare Travesties, the Philosophical and the Popular”

-

“#BlackGirlMagic in Morrison’s Desdemona”

These essays grow from an inclusive classroom that helps students realize they have knowledge and perspectives—including diverse cultural backgrounds and languages—that the literary studies establishment doesn’t yet have and desperately needs. Public Shakespeare fights for those students (often first-gen) who don't come from privilege but have talent, potential, and put in the work.

Developed from a 2021 special feature in Key Terms, this chapter covers the nuts-and-bolts of writing Public Shakespeare essays, especially with students. There are practical directions. Embrace the absurd; mix high culture and low; foreground the comical. Give the cool, quirky, crazy evidence. Keep quotation to a minimum. Make sentences snappy and short. It’s OK to write in the first person. Rain down fire if needed. Make it jokey. Use metaphors, analogies, and other creative gestures. “Peg” your piece to something newsy: an upcoming event, an anniversary, some recent headline, a current controversy.

There are also pedagogical and theoretical considerations. I argue that public writing shouldn’t replace academic writing. The strength of these essays flows from the traditional research papers they’re based on. But public writing is an important change to the mode of articulating scholarship—a skill—rarely addressed explicitly in the humanities. Public writing illustrates what some scholars scoff at (why?): our work has what social scientists call “policy implications,” and opens avenues to what human beings call “happiness.”

Chapter Four

Social Distancing with Shakespeare

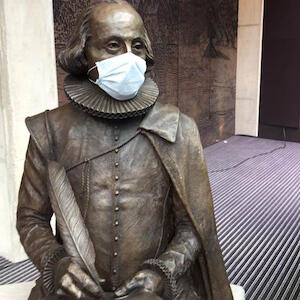

First came the meme to wash hands for the duration of Lady Macbeth’s “Out, damned spot” speech. Soon society was shutting down. “I’m worried about Covid-19 causing theatres to go dark,” tweeted theater-maker @MediocreDave on March 9, 2020. “Not because I’ll lose income, but because we’ll inevitably be subjected to opportunistic Shakespeare scholars making smug but superficial analogies to the playhouse closures of the late Elizabethan plague years.” That’ll be the end of that, I thought.

Then came more than two dozen “Social Distancing with Shakespeare” essays within two months. Their content—Shakespeare born in plague, shuttered theaters prompting his poetry, Romeo and Juliet derailed by quarantine, playwrights sustained by wealthy patrons, disease threatening rival acting troupes, great art created in isolation—is not as fascinating as the questions raised by their method. Why are people cycling experiences with coronavirus through Shakespeare? What do we gain from comparisons between social distancing in Shakespeare’s time and in ours? How might our experiences with social distancing help us better understand Shakespeare’s? How can these examples help us think about academic work in 2020?

The Shakespearean gloss on social distancing shows the power—and pitfalls—of Public Shakespeare. Addressing Shakespearean responses to the coronavirus pandemic and #BlackLivesMatter, this chapter develops an April 2020 essay I wrote during lockdown for North Philly Notes. I come not to bury Public Shakespeare, nor to praise it. I ask what it is, where it comes from, how it works, and why it elicits simultaneous enthusiasm and nausea. What is behind the push in some scholars to filter current events through Shakespeare? What is behind the tendency in others to get annoyed when they do?

In response to these questions, this chapter develops four main points:

-

As an early-modern playwright who often represented medieval and ancient history, Shakespeare built into his texts the practice of engaging the present with the distant past.

-

As artworks that often have scholarly sources, yet are performed for a broad audience of mixed social backgrounds, Shakespeare’s plays have public engagement built into them.

-

The long tradition of modern-dress Shakespearean performance and adaptation provides a model for scholars looking to bring ideas that are old and artistic into conversation with current events.

-

At a time when the humanities are said to be in crisis, Public Shakespeare gives scholars a platform to illustrate the practicality and utility of our field.

There is tremendous energy right now behind public-facing ShakesWork with an ethical if not activist edge. There is also legitimate skepticism of that endeavor. But recognizing Public Shakespeare as more closely related to Shakespearean performance than Shakespearean scholarship helps us understand why, like any show that takes creative risks, some cheer and some hiss.

Chapter Five

Teaching The Show Must Go Online

(with Robert Myles)

On March 19, 2020, eight days after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic—as schools, offices, and theaters were shutting down—The Show Must Go Online launched its first fully online performance: The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Over the next nine months, the group performed each of Shakespeare’s 36 plays online, one each week. Flash forward to March 2021, and first-year college students in the Why Shakespeare?class at Harvard University spent a month watching, studying, thinking, talking, and writing about The Show Must Go Online. They considered how one grassroots organization responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, how new technology is coming into contact with older literature and culture, and the role of the arts during times of trouble.

Developed from my 2020 keynote at Britgrad with Rob Myles, this chapter takes us behind the screens of The Show Must Go Online—from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Bottom’s asshead done with an instagram filter of Donkey from Shrek, to an uncanny performance of Cymbeline on November 4, 2020, after the US presidential election, but before the results were known. “Win or lose,” one of the stars of Cymbeline told a friend the night of the election, “I’ll be getting into drag tomorrow.” We meet the students who studied The Show Must Go Online, hear their stories, and explore some teaching materials to help you and your students create your own stories.

Chapter Six

Historicizing Presentism: From Shakespeare Studies to Public Humanities

What happens when a historicist is confronted with the prospect of presentism? The same thing that happens when a historicist comes face-to-face with anything else: it gets historicized. That’s what I set out to do. I did not expect to come to the conclusion that we need a new academic journal: Public Humanities.

Expanded from my Spring 2019 article in MLA’s Profession, this chapter shows the marriage of historicism and presentism in Shakespeare Studies inspiring a new academic journal, Public Humanities, currently in development at Cambridge University Press. After framing the tension between a historicism trying to be “pure research” and a presentism aiming for “applied research,” the chapter builds to a taxonomy of six varieties of presentism.

Based on ideas first explored in that Profession article, Public Humanities will be an open access journal dedicated to showcasing scholarship from all areas of the humanities in an accessible style and to underscoring the value and impact of that research to society at large. Public Humanities aims to expose a broad audience to cutting-edge research, engaging the public in attempts to address the issues facing society today, highlighting the critical role humanities scholarship has to play, and facilitating scholars as they demonstrate the value of their research. Unapologetically high quality and scholarly, the journal will distinguish itself from other publications with a similar mission by being firmly rooted in the academy, accessible but not journalistic, engaging and topical but rigorously peer-reviewed, and freely available to all.

Chapter Seven

The Public Shakespeare Network

Imagine if, instead of national outlets going to the same “public intellectuals” for pseudo-informed commentary, public writing and programing was part of graduate training in the humanities, so scholars knew what to do when their expertise could inform our understandings of current events. Imagine if, instead of promising projects from upstart young crows lost in the slush piles of open submissions, the university wits among us were to use what little power we have to facilitate new work and distribute opportunities.

The Public Shakespeare Network is a decentralized, grassroots movement supporting communities and scholars looking to think about, with, through, and against Shakespeare and other early-modern literature beyond the confines of academia. Through the #PublicShax hashtag, it creates a space for people from all walks of life to connect with Shakespeare and Shakespeare scholars. For public venues, it offers a go-to resource for finding expertise and ideas. For scholars interested in public-facing writing and programing, but not quite sure how to do it, the Public Shakespeare Network offers three main resources:

-

Guidance for doing public-facing writing and programing: Free and openly accessible how-to tips and tricks from established practitioners walking you through the process of creating different forms of Public Shakespeare.

-

Workshops to help scholars develop and revise public-facing writing and programing: Small group conversations that help aspiring Public Shakespeareans think through ideas at different stages of development, from the concept to the execution.

-

Connections to people and resources that can help bring Public Shakespeare projects to light: The Network is committed to offering introductions and opening doors to help promising projects find the right home.

Chapter Eight

Toward a Center for Public Shakespeare

A lot of us have been agitating. It’s time to institutionalize. We need a Center for Public Shakespeare.

It would fight day and night to make space for Shakespeare studies that belong to everyone. It would be fundamentally democratic: everyone has access; everyone belongs; differences are not just accepted but celebrated, deliberately pursued, and well-funded. The Center would exist to knock down walls and open up doors in Shakespeare studies, broadening the idea of who is in the field and who it’s for. That means that we are never done making space for new scholars, new perspectives, new meanings, and new manifestations.

The Center would connect Shakespeare studies to today’s most pressing questions. It would ask what conflicts are most alive in our world, what new truth can we glean, whom do we reserve empathy for, whom do we leave out, and whom can we turn to for scholarship that brings us closer to our humanity. The Center would be unafraid to ask big ethical questions about Shakespeare: unapologetic in celebrating his praiseworthy moments, unflinching in critiquing his shortcomings. We would not cower from the prospect that knowledge of Shakespeare and his cultural afterlives—including the parts we don’t like—can transform how we understand our world and lead our lives. The Center would be unapologetically activist, asking how knowledge of our literary past can transform our political futures.

It would be a big tent. A diversity of experiences and worldviews would be brought to bear on Shakespeare. The Center would interrogate the familiar and the unfamiliar in Shakespeare studies, the status quo and the unimaginable, and first glimpses of different perspectives. The Center would be radically inclusive and reflect—in the classroom, on the stage, and in administration—the city, the nation, and the world. It would be proudly accessible in all forms, including physical spaces accessible to people with disabilities.

It would bring thinkers together with performers to ask how to think through our twenty-first-century Shakespearean performances and how to perform our twenty-first-century Shakespeare scholarship. The Center would work across the disciplines to bring new scholarly perspectives to Shakespeare, and to ask how Shakespeare scholars can contribute to other disciplines, professions, and policies. It would blur the line between scholarly and creative writing. It would stage performances and adaptations built on knowledge derived from Shakespeare scholarship.

The Center would be mobile, local, digital, and global. It would centralize the decentering of Shakespeare. We would go from the kindergarten classroom to the retirement home asking how Shakespeare studies can deepen and enliven education. Our Mobile Unit would go into local neighborhoods, community centers, schools, veterans organizations, homeless shelters, and correctional facilities, but also into regions of the nation and world that don’t have access to big institutions of higher education. Our Digital Unit would be active on social media. On the model of the Public Theater, we could offer free Shakespeare studies in the park. Perhaps the Center could have regional hubs, Maybe colleges would cheer for their Public Shakespeare team the way they cheer for their football team. The Center would use the heightened mental activity of scholarship and the heightened emotional activity of performance to challenge us to bring more of ourselves to life.

An academic center that is of, by, and for all people isn’t merely a space for scholarship—it’s a living, breathing part of the community. Here Shakespeare creates conversations, inspires action, and explores pressing and complex issues. The Center would partner with communities to ask how Shakespeare studies can help build relationships and connections. It would build community by connecting people through Shakespeare studies and its adjacent scholarly fields.

The Center would coordinate and support the scholars revolutionizing Shakespeare studies by doing the work of Public Shakespeare. It would make space for scholars to connect, explore, and further develop their ideas and their resonance with society's issues, struggles, and futures. It would channel resources to the Shakespeare scholars whose work is most closely bound up with the biggest issues and ideas of our own day.